The disunity characteristic of feudal society disappears in the course of capitalist development and a single national market is formed as a result of which nationalities turn into nations. “Nations,” wrote Lenin, “are an inevitable product, an inevitable form, in the bourgeois epoch of social development.”

The characteristics of a feudal society disappear in the course of capitalist development and a single national market is formed. As a result of this, nationalities turn into nations. “Nations,” wrote Lenin, “are an inevitable product, an inevitable form, in the bourgeois epoch of social development” (1). A nation, like a nationality, has such features as a common territory, language and culture. But as distinct from nationality, it is a durable community of people, and as Lenin noted, it owes its durability to “profound economic factors” (2).

Community of economic life is a key feature of a nation. It is the economy and economic links that unite people living on common territory into a single whole and give them a common language. This makes them into a nation. Economic and political development fosters a common psychology which is manifested in the historical traditions of a nation and in its distinctive culture and mode of life.

Nations are not races. Racial distinctions are certain external biological traits such as the colour of skin, the shape of the eyes, and others. On the basis of these distinctions humanity has been divided into […] basic races: [red], white, yellow and black.Imperialist ideologists claim that the economic, political and cultural level of one or another people, or the position of a person in society depend on racial traits. They talk a lot about the ascendancy of the white race which, they say, has been assigned by nature itself to dominate the “coloured” races. But historical experience and scientific data prove that people of all races have equal abilities. As regards the backwardness of some peoples which do not belong to the white race, it is not due to the colour of their skin or hair, as bourgeois ideologists assert, but to the centuries of colonial oppression by the white exploiters. Now that they have cast off the imperialist yoke, the peoples of the former colonies and dependencies are successfully developing their economy and culture. Particularly rapid progress is being made by the socialist-oriented countries.

Now many have cast off the imperialist yoke, the peoples of the former colonies and dependencies are successfully developing their economy and culture. Rapid progress has been made but much more needs to be done.

Historical Forms of Social Communities

We know that in addition to the mode of production, base and superstructure, a socio-economic formation includes definite historical communities of people, generations, tribes, nationality and nation. Let us examine these communities.

A gens is a historical community of people who are united by blood relationships and certain economic ties, and who jointly protect common interests and combat the elements. The economic basis of a gens was collective ownership and use of the means of production. Its members worked together and together consumed the means of livelihood they produced. A gens was headed by a council made up of all the adult men and women who elected or removed the leaders—elders and military commanders.

In the initial stage of the development of the gens its members were those whose descent was reckoned through the mother (matriarchate). Later when the labour of men became socially more important, particularly with the spread of stockbreeding and tilling, the matriarchate was replaced by patriarchate. The father tried to leave the family property to his heirs and the gens’ property gradually became separated from collective, clan property.

Several gentes would unite into a tribe characterised not only by a common ancestry, but also a common language and territory. The gens and tribe existed under the primitive system and played a tremendous role in the development of society: people settled almost throughout the planet and laid the foundation for mankind’s material and spiritual, culture.

With the development of production and the rise of a class society and the state, blood relationships gradually fell apart and the gens and tribe gave way to a new historical community of people—the nationality. But the survivals of the tribal system persist for a long time and in some Asian and African countries they have remained to this day as a result of the imperialist colonial policy.

As an historical community of people nationality is more typical of the slave-owning and feudal systems. Unlike the gens it is not based on consanguinity, but above all on common territory, language and culture. Nationalities emerged mainly as a result of the union of kindred tribes.

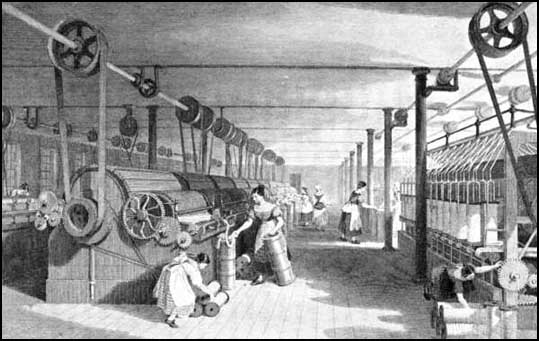

The common territory and community of language and culture typical of a nationality rested on a definite material foundation—natural, primarily agricultural economy with no social division of labour worth mentioning, peasant crafts and, later, manufacturing. Yet a nationality was not a sufficiently durable community of people because under the slave-owning system and feudalism the development of country-wide economic ties, without which close, stable connections between people could not emerge, was impossible. There were, of course, exchange of commodities and markets in the slave-owning society and under feudalism, but they were merely of local importance and were incapable of overcoming economic and political disunity.

Some nationalities, that emerged in the slave-owning system and in a number of countries under feudalism, have remained under capitalism and socialism but they have acquired specific capitalist or socialist features.

Although the working class and other sections of working people make up the overwhelming majority of a nation in capitalist society, it is the bourgeoisie that plays the dominating role in it. All the means of production, state power and the mass media are in its hands. That is why bourgeois economy, politics and ideology in the main determine the image of a nation in capitalist society. The domination of economically and militarily more powerful nations over the weaker ones is consistent with the laws of development of bourgeois nations. This accounts for the fact that the development of nations under capitalism is inseverably connected with the intensification of the liberation struggle of the oppressed peoples. The national question, i.e., the question of the ways and means of the liberation of the oppressed nations, abolition of national oppression and the establishment of equal relations between nations is particularly acute under capitalism and is one of the main issues of social progress.

The content of the national question is not the same at various stages of capitalist development. In the period of the rise of capitalist society this question did not, as a rule, transcend the limits of individual stales. It was Russia, Austria-Hungary and some other multinational states, where some nations oppressed others, that were the main arena of the national liberation struggle. There the national question was in essence a question of national minorities, of their struggle for liberation and the right to establish their own statehood and economy, and foster their own culture.

National relations changed with the advent of the epoch of imperialism. The world split into a handful of dominating nations—the more advanced capitalist countries—and the majority of colonial and dependent nations and countries. Lenin regarded the division of nations into those that oppressed and those that were oppressed as “basic, significant and inevitable under imperialism” (3). The colonial system of imperialism came into being. Having entered the imperialist stage, capitalism, which at the dawn of its history helped the peoples to throw off the feudal and clerical yoke, turned into the greatest oppressor of nations and mercilessly suppressed the independence of peoples. Thus, the content of the national question changed and became much broader. It ceased to be an internal matter of a state and turned into an international issue bearing on the future of hundreds of millions of people.

Under imperialism the national question is no longer a question of national minorities within the boundaries of one state, but a national-colonial question. Above all it is a question of the people’s struggle against the colonial rule, of their liberation and development along the road of progress.

Noting the importance of the national question, Marx, Engels and Lenin did not regard it, however, as the fundamental question of the revolutionary movement. They always subordinated it to what is the most important in Marxism—the teaching of the dictatorship of the proletariat—and viewed it from the standpoint of the interests of the international proletarian movement, the struggle for peace, socialism and social progress. They proceeded from the assumption that the national question as a whole could not be solved under capitalism, but only under the rule of proletariat, in a socialist society.

Lenin discovered two contrasting trends in the development of national relations under capitalism. One of them is manifested in the awakening to national life and in national movements, in the struggle against all national oppression and in the rise of national states. The other is expressed in the development of relations between different nations, in the destruction of national barriers, and in the formation of a single economy, of a world market. The first trend is predominant in the epoch of rising capitalism, the other, in the epoch of imperialism.

Both trends are consistent with social development and are progressive in terms of their inner historical meaning. But under capitalism they assume ugly forms that are incompatible with their objectively progressive content. Imperialism creates giant international banks and trusts and an all-embracing world economy, and increasingly unites, internationalises society’s economic, political and cultural life. But this drawing together, “rapprochement” of nations under the domination of capitalist monopolies can take place only through violence, colonial plunder and the oppression of peoples by others that are more advanced and powerful. Under imperialism whole nations, big and small, and vast continents fell prey to the colonial expansion of a handful of imperialist predators who used the most brutal methods to crush all the efforts of the oppressed peoples to liberate themselves. It follows that the trend of the nations to draw together, to unite under capitalism directly contradicts the trend towards national independence and the formation of national states.

The above trends in the development of national relations are reflected in bourgeois ideology and policy and manifest themselves in the form of nationalism. Being intolerant of all manifestations of bourgeois nationalism, Marxism-Leninism at the same time draws a line between the nationalism of the dominating nations (Great Power chauvinism and racialism) and the nationalism of the oppressed nations. The ideology of Great Power chauvinism and racialism which justifies the domination of one nation over another is absolutely reactionary and is unconditionally rejected by the working class. On the other hand, the nationalism of the oppressed nations contains the progressive tendency of fighting for independence, against imperialism, and is therefore supported by the proletariat. “The bourgeois nationalism of any oppressed nation,” Lenin wrote, “has a general democratic content that is directed against oppression and it is this content that we unconditionally support” (4). Such, for instance, is the nationalism of some Asian and African countries today. This nationalism owes its progressive nature to the struggle against imperialism and colonialism, against feudal reaction and backwardness, a struggle which awakens the self-awareness of the people, of millions of peasants in the first place.

It should not be overlooked that the progressive trend in the nationalism of the oppressed nations cannot be permanent. It is transitory because the historically progressive role of the national bourgeoisie in the national liberation movement is also transitory. Hence, when it supports the liberation struggle of the oppressed peoples, the party of the working class strives to rid the working people of the influence of nationalism, for bourgeois nationalism is incompatible with proletarian internationalism. By disclosing the decisive role played by the class struggle in any social movement, including the national movement, and appealing for the unity of the proletariat of all countries, a Marxist party overcomes the ideology of bourgeois nationalism and asserts proletarian internationalism in the consciousness of the working people.

Sources:

1) V.I. Lenin, “Karl Marx”, Collected Works, Vol. 21 p. 72.

2) V.I. Lenin, “The Right of Nations to Self-Determination”, Collected Works, Vol. 20 p. 397.

3) V.I. Lenin, “Social Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination”, Collected Works, Vol. 22, p.147.

4) V.I. Lenin, “The Right of Nations to Self-Determination”, Collected Works, Vol. 20, p. 412

Categories: History, International, Science, Theory, U.S. News, World History

Juan Perón and Social-Fascism in Argentina

Juan Perón and Social-Fascism in Argentina  Pacifism: How to Do The Enemy’s Job For Them

Pacifism: How to Do The Enemy’s Job For Them  Systems of Stratification: Gender in Capitalist Society

Systems of Stratification: Gender in Capitalist Society

Tell us Your Thoughts